From the Archives: Food and Community — Vignettes

I’ve been reading some memoirs lately about food and cooking as a pathway to self-enrichment. I’m not sure why, really, but I blame it on my Kindle, which recommended a book about a woman with a troubled upbringing, who went to Wesleyan University and later the Culinary Institute of America and now blogs about motherhood and “cooking the world” while living in Tulsa, OK. I don’t know why the algorithm produced this book for me because I don’t have kids and don’t cook, but my sister went to Wesleyan and I have a blog and I visited Tulsa once to write about the Philbrook Museum of Art, which two years ago hosted a communal dinner showcasing ethnic foods from around the world organized by the author. From there, it’s been a slippery slope to reading about Sandra Bullock’s sister and her post-Hollywood career baking in Vermont that she parlayed into a food blog and TV appearances, and a former journalist/corporate VP who enrolled in Le Cordon Bleu to regain her sense of self.

Perhaps because Thanksgiving is around the corner—but more likely because I’ve been traveling and missing my husband’s excellent home cooking—I’ve been musing on the meaning of food and community.

In the context of our cultural organizations, that translates to the prepared foods we serve in our cafés and bars to fortify audiences for more gallery hopping or the next orchestral movement. The posh food we provide our patrons at lavish gala dinners. The potluck meals we share with our colleagues to celebrate milestones. The celebrity chef gourmet feasts we raffle to the highest bidders. The snacks and caffeinated drinks we offer to volunteer committees to make meetings more palatable. The content rich, intimate salons we enjoy with artists and critics over pasta and red wine. The staples and leftovers we store in our break room kitchens.

Each of these experiences serves a function, sets a mood, communicates a message and reflects who we are, as persons and as institutions. Above all, each gathering fosters a sense of community, with food at its foundation.

# # # # #

The Community Meal. Photo credit: Andy King © 2014, courtesy of Public Art St. Paul

I’m drawn to the spirit of community created by the Slow Food Movement, founded over 25 years ago by Italian Carlo Petrini as antidote to today’s pervasive fast food culture in order to reconnect local farmers and food producers with consumers. The emphasis here is on the local, raising fresh foods germane to the local environment and preserving regional culinary traditions. It has spawned the growth of farmers markets, artisanal food purveyors, and a new class of chefs and restaurateurs following in the footsteps of Alice Waters, all of whom place a high value on the environment, sustainability and quality of life in their communities.

As defined by Slow Food International, food communities represent a “group of small-scale producers and others united by the production of a particular food and closely linked to a geographic area. Food community members are involved in small-scale and sustainable production of quality products…[reflecting] a new idea of local economy based on food, agriculture, tradition and culture.”*

This is exactly what food writer Christine Muhlke discovered when she was asked by The New York Times to study the slow food and locavore movement in the US. Wherever she traveled, she found a network “of producers, of customers, of eaters and enthusiasts…[connected by] a shared interest in food.” As Muhlke related, community in this context is “built upon conversations.”^ Isn’t this the kind of engagement we seek for our own organizations—local communities bonded by meaningful exchange and discourse?

That potential for connection and dialogue inspired artist Seitu Jones last October to stage The Community Meal, a communal dining experience attracting over 2,000 residents of St. Paul, MN. The luncheon meal and dining table, which extended over half a mile on a street in the city’s Frogtown neighborhood, was made possible by Public Art Saint Paul and 500 volunteers. Jones’ work, which purposefully brought together food producers and institutional partners with the public, sparked discussion about local food systems, accessibility and affordability of fresh food, eating habits, gardening and family recipes. Food as community glue.

# # # # #

I trekked with a friend over to Williamsburg, Brooklyn the other day to visit the newly opened Museum of Food and Drink, aka MOFAD. The inaugural show illuminates the interplay between scent and taste, and the work of industrial food chemists, who seek to recreate or enhance natural flavors in the lab. It’s part science, part children’s museum in feel and experience, a tad heavy on interpretation and wall text for my taste (yes, pun intended), and regrettably, there was no food art to enhance the experience. The space is beautifully designed and lit, with well-crafted modern furniture and display cases, and the friendly gallery attendants are cheerfully attired in denim aprons. There was no food to sample, only tiny pellets dispensed like bubble gum to demonstrate the difference between real flavors and manmade. In hindsight, I'm not sure what I expected—perhaps a working demonstration kitchen producing all sorts of fragrant delights, since MOFAD’s founder is the visionary chef Dave Arnold. Alas, there was no breaking of bread with other guests on the day we visited.

# # # # #

In my formative years, I was a mad baker. Before I was old enough to go out unchaperoned with my friends, my Friday and Saturday nights were spent in the kitchen concocting all manner of cookies, cakes, breads and muffins (I don’t like pie). I progressed to the point where I intuitively knew the ratio of dry ingredients to wet and didn't need to measure, and could tell by touch and feel when the batter or dough was ready. My family happily consumed whatever I made: chocolate chip, molasses, and peanut butter cookies; brownies and blondies; devil’s food cake, lemon cake, and plum torte; peach cobbler and gingerbread; blueberry and banana muffins; sour cream coffee cake and Irish soda bread; English muffins and pita bread; sour dough rounds and my grandmother’s raisin bread.

There is nothing like the rich smell of chocolate anything in mid-bake, or the physicality of kneading elastic, living bread dough and witnessing gluten and yeast work their magic overnight. Baking was something restorative I did for myself and something that allowed me to share myself with others. It was a source of pleasure—in the ritual and craft of making, and then in the giving and sharing. Ironically, in my early 30s, I was diagnosed with a gluten allergy and the mysterious ailments that had plagued me for years finally subsided when I eliminated the offending grains from my diet. This markedly changed my baking habits, because no matter how many food chemists work to improve gluten free products, they’re not the same as the real thing, as MOFAD’s exhibition made clear.

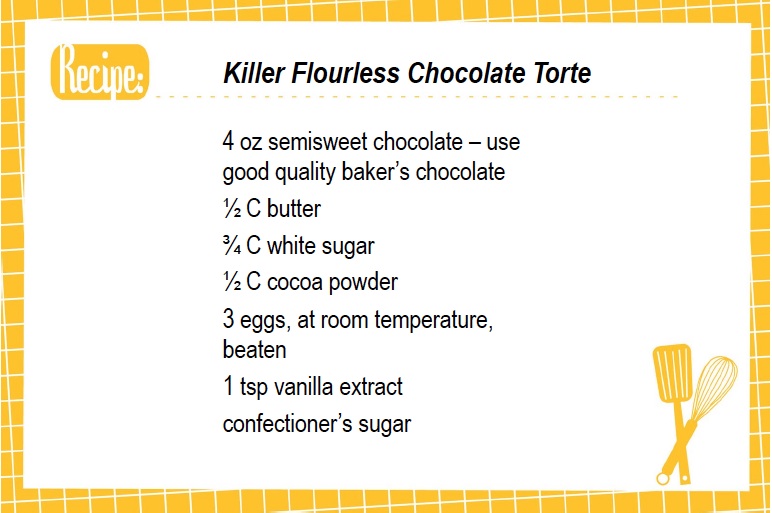

Now I only bake for birthdays and holidays as gifts for family, friends and colleagues. So, in the spirit of Thanksgiving, I offer my edible contribution to the genre of food memoirs with a recipe for a gluten free dessert that will make you the hit at any gathering. Here's to breaking bread with your community.

Citations

* Slow Food International. "Slow Food terminology." Web. 21 Nov 2015.

^ Muhlke, Christine. "Growing Together." The New York Times Magazine. 8 Oct 2010. Web. 21 Nov 2015.