Last summer, I gave myself something I had long dreamed of – I took a mini sabbatical for three months. My intent wasn’t to retreat or laze about soaking up the sun (although I did some of that) – it was to learn and reflect. I spent most of my time reading to inform my work with cultural organizations, exploring subjects one never has enough time for when deadlines loom. I read books on leadership, change management, organizational theory, group dynamics, mindfulness, salesmanship, social media and design thinking, among others.

What most captured my attention was design thinking, the concepts and practices of which I was introduced to during the year I spent at the Rhode Island School of Design as interim head of advancement. I still remember one of my first conversations there with a group of artists and designers on the faculty. They were fine-tuning a corporate sponsorship proposal about a methodological approach to teaching that incorporated design thinking. It felt like everyone else in the room was speaking a different language! That’s another story, but part of this one, too – to demystify what may seem foreign, but really isn’t.

Design thinking is a system-based, iterative, group process intended to uncover new ideas to address challenges and solve problems. Originally conceived back in the late 1960s to aid the fields of engineering, architecture and urban planning, it was introduced to the business world in the early 1990s by David Kelley. He’s a mechanical engineer, entrepreneur and Stanford University professor of design, best known as the founder of IDEO, an award-winning global design firm based in San Francisco.

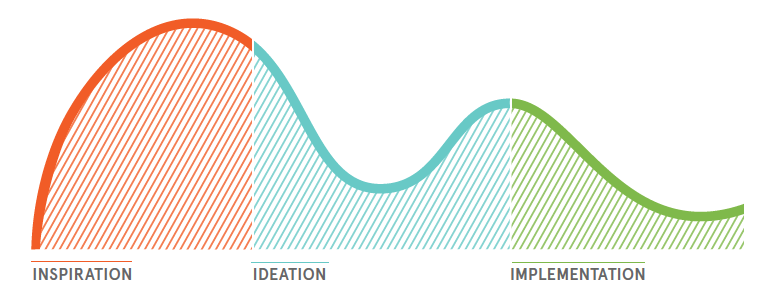

IDEO practices and proselytizes human-centered design, a non-linear, design-oriented approach focused on the end-user that can be applied to nearly any creative endeavor (how to design a new product, service, space or experience, for example) and is especially useful in innovation. The best books on design thinking applicable to organizations describe anywhere from five to seven stages of progressively linked actions, but IDEO has simplified its process to three – inspiration, ideation and implementation – which I’ll explain in a moment.

“Human-centered design relies on our ability to be intuitive and to recognize patterns, to construct ideas that are emotionally meaningful as well as functional, and to express ourselves in media beyond words or symbols.”

IDEO believes so strongly in this human-centered approach that it created, in partnership with Acumen and NovoEd, a free, online course to train social entrepreneurs in design thinking to tackle the world’s toughest problems.

Recognizing that learning from a book is one thing and putting lessons into practice another, I accepted an invitation to participate in the course. And since design thinking relies heavily on collaboration and team-based effort, I invited Providence colleagues Jane Androski and Ann Woolsey to join me. Jane is co-founder of Design Agency, a nonprofit branding and graphic design firm, and Ann is an art historian and museum consultant. We’ve been getting together every week since mid-August to unpack the coursework and apply what we’re learning to a real life situation – in this case, how to design a retail experience for locally-raised, fresh foods targeted at a low income population.

How, might you ask, could Jane, Ann and I tackle such a challenge when our professional expertise is in the cultural sector? That was one of my Eureka moments about design thinking. I never previously understood how design firms like IDEO could address such disparate issues for a wide range of clients. IDEO has worked in the fields of digital learning, hospitality, medical products, food, financial services…you name it. I’m accustomed to working with cultural and educational organizations as a field and subject matter expert. What IDEO excels at is applying the practice of design thinking to formulate new ideas and achieve new solutions in any field.

The comparison that comes to mind is a more traditional McKinsey-like approach to management consulting, where the consultants aren’t subject matter experts either, rather practitioners of a highly developed and road-tested process that helps organizations to change. Design thinking doesn’t seem as formulaic to me as McKinsey because it’s people-focused and emphasizes the stakeholder over the corporate product, service or bottom line. (And I'm predisposed to that way of thinking, especially after my work with Magnetic Museums.)

IDEO’s process operates from a set of shared assumptions – that there is merit in experimentation and learning from failure; that making something physical trumps conceiving of something theoretical; that everyone is creative and all ideas have value; that demonstrating empathy is key to this work, as is remaining optimistic; that not knowing the answer and being open to learning leads to new discoveries; and that iterating ultimately produces the finest solutions.

There's a great deal of utility in applying design thinking to cultural sector issues, and many organizations are already doing so, with or without this labeling. What follows is my condensed version of IDEO’s process, adapted from its Field Guide to Human-Centered Design:

INSPIRATION

The first phase involves framing your inquiry to allow for open-ended discovery rather than ready answers. It also involves research and learning directly from the people who represent your target market or who ultimately will be affected by your efforts – in other words, your end-users. For cultural organizations, that could be program participants, audience members, patrons, K-12 students, teachers and the like.

Here’s how to begin:

- Articulate the problem you’re trying to solve – what IDEO refers to as the “design challenge” – in a way that allows for flexibility in your exploration and ultimately leads to impact. This requires framing the task ahead neither too broadly nor too narrowly, which is more difficult than it sounds and takes some practice to do well.

- Assemble a cross-disciplinary team of “thinkers, makers and doers” who bring different perspectives and experiences to the challenge. If you’re a theater seeking younger audiences, for instance, include on your team a dramaturge, marketer, set builder, educator, comptroller, fundraiser and box office attendant to ensure that diverse viewpoints inform the problem-solving.

- As a team, develop and execute a plan that outlines what you need to learn, the preparatory research you need to do to better understand the problem at hand, and with whom you should speak to provide hands-on insights. Make sure to include “users” on all points of the spectrum, especially the extremes, i.e., the one-time attendee vs. the repeat subscriber. Break into small groups and divvy up the tasks.

- Then go out in the field and conduct interviews with stakeholders, one-on-one and in groups, preferably in their own environments, such as their places of business, homes and neighborhoods. Be attentive to their surroundings and, with their permission, record conversations via hand-written notes, drawings, video and photography. Note the tactile, visual nature of the design thinking documentation process.

IDEATION

This next phase involves reflecting on your fieldwork, analyzing and then synthesizing the collected data to identify recurring themes and important insights. Taken together, these provide a guided pathway for brainstorming ways to address your challenge. I’ll delve more fully into this second phase, followed by the third phase of implementation, in my next post.

Citations & Image Credit

The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design (1st ed.). San Francisco, CA: IDEO.org, 2015.

An Introduction to Human-Centered Design. San Francisco, CA: IDEO.org + Acumen, 2015.