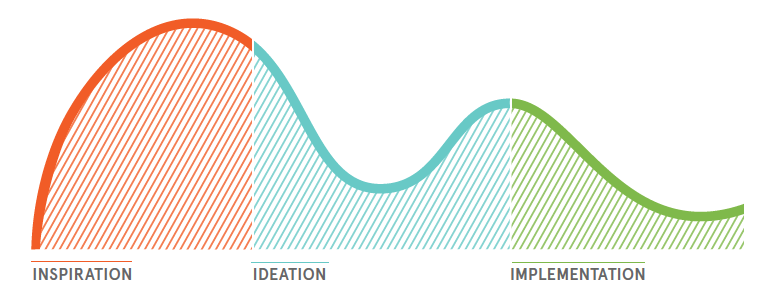

My prior two posts, found here and here, introduced the concept of human-centered design advocated by IDEO,* a global design firm that helps organizations to grow through innovation. I reviewed the first and second of IDEO’s three stages of design thinking, inspiration and ideation. To quickly recap, these include:

Inspiration

- Framing the design challenge;

- Assembling a diverse team to tackle the challenge;

- Identifying what learning is needed to address the issues at hand; and

- Conducting field and other research.

Ideation

- Sharing, reflecting on and articulating insights from the research;

- Asking nuanced questions informed by the research that go to the heart of the problem;

- Brainstorming to uncover workable solutions; and

- Rapid prototyping for immediate feedback.

Now we’re ready to tackle the third phase, implementation. The good news is that this will be familiar to those of you who have done operational planning, especially in conjunction with strategic planning. This phase involves mapping action steps: identifying resources and needed personnel, projecting expenses, determining a rollout plan and timeline, launching a pilot and evaluating results. It also continues to emphasize the benefits of interdepartmental teams – what my co-author and I advanced in Magnetic as “inviting the outside in” – to ensure that different perspectives and external voices are heeded as you build towards launch.

IMPLEMENTATION

I’ve attempted to summarize the implementation process in a logical order, but as with all things design thinking, the sequence of steps can fold back on itself returning to any stage as you keep iterating, fine-tuning and learning as you go. Tackle the below as a team, assigning leaders to guide and “own” each activity.

- Finesse your prototype and then head out into the world to test it live with a select group of end-users. As noted in an earlier post, prototyping can take many forms (i.e., storyboards, games, role playing, mock-ups, etc.), so choose one best suited to your design inquiry. If you’re testing a new after school program idea for youth, for example, lead a group of participants through a condensed or partial version of the program to solicit their opinions and watch their interactions. Record and use this pointed feedback to refine the program design and ready it for a pilot.

- Create an 18-24 month action plan – what IDEO calls a “roadmap” – detailing the steps that will take your project through and beyond launch. Chart this on a calendar accessible to the entire team and keep it updated as shifts in timing occur. (IDEO advocates for a big, physical, centrally located calendar that all team members can edit using, you guessed it, Post-its®! But a digital version with multiple users can be just as effective.)

- Think through all of the who-what-when-where-how considerations to identify the human, financial and physical resources needed for implementation. This may include additional staff or consultant expertise, institutional partnerships, office and/or program space, IT infrastructure, equipment and supplies, permits and insurance, strategic outreach and promotion, plus seed and sustainable funding (both raised and earned revenue streams). A good overview on business planning by the National Council of Nonprofits, found here, can help point you in the right direction.

- Define what success will look like so your goal is always front and center, a visible guidepost against which to measure results. Identify the quantitative and qualitative metrics you will use to monitor your progress, and put corresponding data management systems into place at the project’s outset.

- Prepare and institute your fundraising and marketing campaigns to reach targeted audiences. Use persuasive storytelling techniques to secure stakeholders committed to your success and loyal to your efforts.

- Invest money judiciously in the essentials, like personnel and equipment, then launch your project as a pilot for a defined period of time (i.e., 6-12 months). Make sure to collect data and capture human-focused stories throughout, and evaluate outcomes to determine what works and what needs improvement. With this added knowledge, you’ll be equipped to head into full implementation mode using a similar process as above to scale growth.

True design thinkers advocate for continuous iteration, which can be considered the contemporary equivalent of the Japanese management theory of “kaizen” or continuous improvement. In other words, the journey is never quite over because ongoing or incremental change brings opportunity for heightened impact.

To paraphrase IDEO president and CEO Tim Brown in his now signature article from 2008 in the Harvard Business Review, design thinking is methodology more strategic than tactical. It fosters a “team-based approach to innovation…[that] feature[s] endless rounds of trial and error…[blending] art, craft, science, business savvy, and an astute understanding of customers and markets.”^ Today, Brown asserts, mastering the art of design thinking leads to creative leadership at all levels, providing a competitive advantage to any 21st-century organization. Isn’t that what we all strive for?

With my consciousness raised, I see the application of design thinking everywhere, such as this recent article in The New York Times about designing backpacks in the digital age. To shape their understanding of user needs and wants, designers didn’t just talk to students and hikers, but other people who carry things on their backs, including the homeless. That’s certainly going to the extreme, but brilliant in its approach.

I’ve often found that insights come from the most unexpected places. Human-centered design gives you the tools to uncover new ways of seeing and doing focused directly on those you seek to engage – your constituents. I hope my demystification of the process will encourage you to try this. And I’d love to hear from those of you in the arts who have effectively instituted design thinking as an instrument of organizational growth.

Citations

* The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design (1st ed.). San Francisco, CA: IDEO.org.

^ Brown, Tim. “Design Thinking.” Harvard Business Review, Jun 2008: p. 86. Print.