In my prior post, I introduced as relevant to nonprofit cultural enterprise the concept of design thinking championed by IDEO, a global design firm committed to design’s positive impact on humanity. I reviewed the first of IDEO’s three stages of design thinking, inspiration, which includes:

- Framing the design challenge;

- Assembling a diverse team to tackle the challenge;

- Articulating a plan that addresses what learning is needed; and then

- Conducting field and other research.

Now we’re ready to tackle the second phase, ideation.

Marilyn in Post-Its, by Valtech Sweden office

Ideation

This stage involves analysis and synthesis of the data gathered from research and fieldwork, and then applying imagination and creativity to address what you’ve discovered. Here’s how:

- Re-assemble as a team and share real stories from the field; actively listen to one another and reflect on what you’ve learned. Transfer salient points and insights to post-it notes – design thinkers love Post-its® and Sharpies, the more colors, the better! – and then stick them up on the wall for everyone to see.

- As a group effort, rearrange the Post-its® into categories and identify the top three-to-five emerging themes. Then succinctly articulate “insight statements” – things you’ve learned that will be important considerations in the design phase.

For example, say your design challenge is to enhance youth participation in your after school programs, and your discovery process has revealed that young people in your community (1) don’t know much about your organization, (2) prefer to hang with and get information from friends about what to do outside of school, and (3) haven’t had much exposure to the arts. (These are “insight statements.”)

- Translate these insights into “How Might We” (“HMW”) questions that reflect what you’re learning and that go to the heart of the problem you’re working to solve. Resist dictating a specific pathway and shape questions that will allow for a number of solutions or innovations to bubble up.

Using the above example, you could frame the design challenge by asking, How might we develop and promote program offerings to engage youth who are unfamiliar with art and artmaking?

- Now it’s time to pass around some chocolate and start brainstorming to elicit myriad ideas that address the design challenge and HMW questions. Record the ideas in words, drawings, charts – whatever gets the point across – using a whiteboard, flip charts, more Post-its®, magazine pages cut up into collages, etc. All ideas have merit, so don’t edit at this stage, and as IDEO urges, go for quantity over quality. Also emphasize pictures over words, which help to bring ideas to life.

- Now step back from your design wall to digest and process all of this data to notice where there is convergence. Then synthesize or “bundle” the best ideas and consolidate them into one or two concepts that can be tested. Don’t forget to refer back to the original challenge to ensure that you’re arriving at potential workable solutions.

- Use “rapid prototyping” to concretize your best ideas and get immediate feedback from team members to aid your R&D process. Designers utilize various tools to help make the conceptual real. Choose those that best serve your design challenge, as well as those your team is skilled at or can master – such as storyboards (freehand drawings supported by short, explanatory texts), customer journeys (narrative writing and storytelling using personas), role playing (acting and simulations), mock-ups (physical models graphically designed or sculpted from low cost materials, like construction paper and tape) and experience maps (a combination of all of the above and more).

Mocking up rapid prototypes: Boise State University's LaunchPad program for student entrepreneurs

Although perhaps not conceived as such, the Fleisher Art Memorial engaged in a human-centered design process when it set out to attract increased participation by neighborhood residents in its on-site, art-making programs. The Fleisher is located in Southeast Philadelphia, an ethnically diverse, low-income community populated by Asian and Latin American immigrants. The art center had specifically designed programs to attract children and families to its facility, yet the community just wasn’t showing up. Fleisher staff wanted to know why and what could be done to enhance engagement.

With funding from The Wallace Foundation and aided by outside researchers, an interdepartmental team at the art center began its inquiry with a baseline study to understand the current audience. Then they held focus groups with adults and teens from the neighborhood to learn how the Fleisher was perceived. They also learned what locals wanted from the organization, summarized in three key findings:

- Come to Us: Residents wanted the Fleisher to be physically present in the community outside of the art center and to build relationships directly with neighbors;

- Show Us: Residents wanted the Fleisher to use community centers and neighborhood events to present demonstrations and teach them about art and artmaking, especially connected to their native cultures; and

- Welcome Us: Residents wanted the Fleisher to build trust with the community and make the art center more hospitable and accessible to all.

Armed with this new knowledge, the Fleisher staff transformed its internal culture through institutional planning and best practice training in diversity, communications and visitor services. The art center also transformed its external outreach through organizational partnerships and by ensuring a strong staff presence at neighborhood events. Plus, they prototyped new offerings at community festivals and probed for residents' feedback, which they used to fine-tune activities. The end result? Participation by teens and kids in on-site programs has increased more than 10% since the baseline study, and people from Southeast Philadelphia now represent 25% of all students in Fleisher art classes, an increase of 5%, matching area demographics. A full description of the art center’s design challenge, process and outcomes is detailed in a case study published by The Wallace Foundation.

Implementation

The final phase in IDEO’s process, implementation, involves live testing prototypes, seeking honest critique from your target audience, iterating and refining until you’ve hit upon a solid solution to meet real needs, business planning, piloting the new idea and finally taking it to market. I’ll bring it all home in my next post.

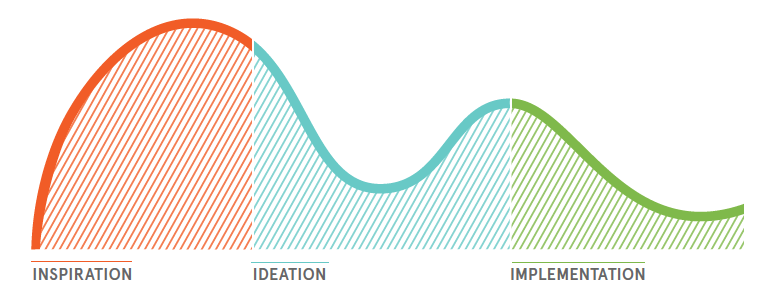

Disclaimer: Let's pause for a moment to address the notion of phases, which implies a straightforward, linear, continuous, one-foot-in-front-of-the-other process. In actuality, design thinking is non-linear, and moves back and forth among the three phases in whatever way makes sense for a particular project. This is what IDEO's graphic is seeking to convey, with progress that may be up and down, divergent, convergent and fluid.

Warning: For those of you who prefer things neat and tidy (like me!), design thinking can be messy, so be prepared to surrender some control and live in discomfort for a bit. Trust me, the freedom this engenders is worth it!

Citations

The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design (1st ed.). San Francisco, CA: IDEO.org, 2015.